On gaming backlogs, or what Umberto Eco's private library teaches us about them

We all eventually start thinking how we can put an end to our backlogs. This is not the right question though.

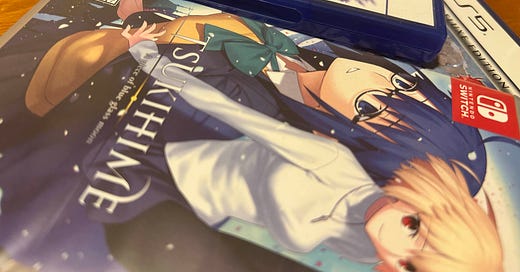

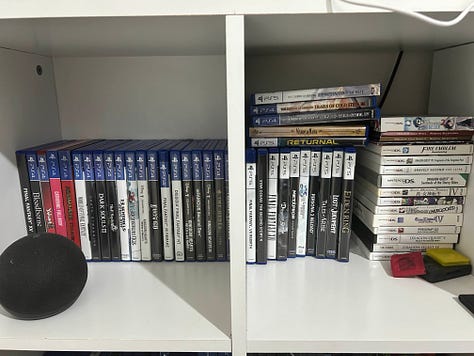

I have been confronted by a scary realization. Maybe, I shouldn't buy more games. As expected from anyone who really likes them, I have too many games. Physical and digital. New and old. And to make my case even more difficult to solve, the pile of games I have waiting for me is mostly composed of 50-plus hours titles; all the potential RPG classics which I don't want to miss.

An increasing backlog of games is a shared experience among those who are at least enthusiasts of the medium. Not everyone enjoys them though. For most, Backlogs are hydras with which they constantly battle; and like said creature, every game that is finished turns into two, three or even four new ones that are added to the pile. There isn't a consensus on how to deal with these cumulative games. Some advocate for "scientific" methods to complete games in the most optimal and quick way; others defend that they shouldn't be a concern, just a sign that we are leaving and searching to experience whatever we can. In the end, we are all trying to understand whether buying more games before finishing old ones on the list is a problem or not.

Having too many games isn't, however, the first reason why I have questioned myself about my behavior toward things —an interpellation that seems a constant event. After I had finished college, I stopped to look at the shelves in my parents' house. Books. I had a lot of them. I still do. Moving from there to a considerably smaller place made unsustainable to keep all of them though. Owning a great number of books is, more often than not, seen with better eyes, a condition described with more positive adjectives than having shelves and more shelves with the big PlayStation hits from the last fifteen years. Even so, I believe – I hope – most people who like books have wondered whether they should own fewer books, be more selective about the titles they decide to spend money on. And like myself, they must have heard about Umberto Eco's library.

A huge name in the field of semiotics, the Italian professor Umberto Eco was part of a generation of intellectuals which now very few are still alive. The Name of the Rose might have surpassed its creator in fame, but Eco's work goes way beyond stories about gruesome deaths in a monastery. His was a life of erudition. A life expressed through learning and books! Although Eco's relationship with books became a kind of intellectual motivation discourse for justifying the monthly book hauls people share on social media (Tsundoku goes right after it as the Japanese version of Eco's library), the author had an interesting approach to unread books which can help us think about unplayed games.

In his essay Borges and My Anxiety of Influence, while he explains his own relationship with Jorge Luis Borges, Umberto Eco clarifies that, for him, a private library shouldn't be “a place to keep books one has already read but primarily a deposit for books to be read at some future date, when one feels the need to read them.” These are the words from a man who allegedly owned around forty thousand books. Holding to them is not, for Eco, a source of anxiety or pressure. He doesn't need to read them. At the same time, he says that, in a curious movement, we might read them—in a nonconventional way.

Eco says that “the day eventually comes when, in order to learn something about a certain topic, you decide finally to open one of the many unread books, only to realise that you already know it.” For him, this is not the result of mystical event nor the product of methods to quickly scan pages, making the most out of a few minutes of reading. The author of The Name of the Rose finishes this segment by clarifying that “the true explanation is that the moment when we opened it [said unread book], we have read other books in which there was something that was said by that first book, and so, at the end of this long intertextual journey, you realise that even that book you had not read was still part of your mental heritage and perhaps had influenced you profoundly.”

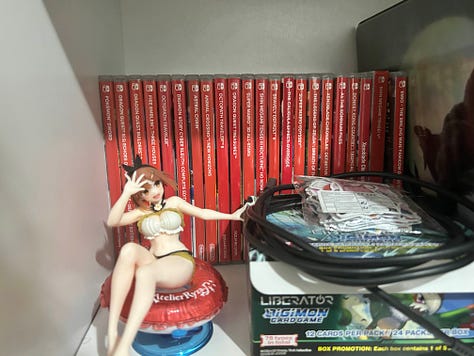

Facing our backlog might fluster some of us. I certainly do. I know the mixture of feelings imposed over me when I see the new additions to my Steam library; anxiety regarding the new one hundred hours RPG I just bought but requires me to play other three games before I can jump into it. The eventual moment of experiencing these titles excites me. Just like Eco suggested for libraries, a backlog of games can be understood as a deposit of possibilities.

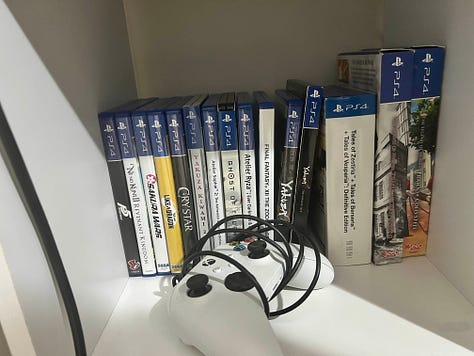

And just like Eco handles his books, we can manage our games. The number of new releases seems to increase every year and playing all of them is not feasible. But a new fan of soulslike might feel extremely comfortable and curious realizing, once playing the game in the bundle they bought after getting too excited about Elden Ring, that Dark Souls II is familiar. And they might understand more of Dark Souls III when they finally play Bloodborne.

Perhaps this is not a good rationale to be followed by those who aren't curious about the medium. Some players are like casual readers; from time to time, they buy a book at an airport. A quick distraction. At the same time, I don't think that reflecting on the nature of a backlog – nor a library for that matter – means something to them. They have their own type of library; their own collection of things. No, understanding how to better approach our backlogs is our kind of problem. A conundrum moved by curios eyes, eyes that are drunk on the everlasting desire to dive into countless experiences the world around them can provide.

If you enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing to receive the new ones once they are published.