Language and Truth in Anatomy of a Fall

I don’t usually write about movies — at least I don’t plan on — but if you want to receive my newest pieces on games, books, and, hmm, movies(?), consider subscribing to my Substack. It is completely free!

From the terrific performance of Sandra Hüller as Sandra to the charismatic Snoop, the dog who captivated everyone by literally playing dead, a lot has already been said about Anatomy of a Fall. I don’t think we have exhausted the list of interesting topics that come with this movie, such is the power of great pieces of art. Far from having keen eyes to analyze the quality of the craft, I can’t help but want to write a few words about this movie. Thus, here I am to talk about the encounter of language and truth in Anatomy of a Fall.

Truth is a matter of debate and constant expenditure of energy in Anatomy of a Fall. It is a trial movie, where Sandra, a famous fiction writer, is charged with having murdered her husband, Samuel. In a production like this, most of the events take place in the courtroom and what happens outside is, in one way or another, tied to the judgment of Sandra. Ironically, the truth the movie is concerned about is not regarding the death – who, why, and how –, which won’t stop the characters and narrative from looking for clues to prove that Sandra is guilty or innocent.

The process through which Sandra and her son Daniel go through is stressful, pushing them to the edge.

The trial serves, at the same time, to show us how truth is a product of negotiations between several actors. The courtroom becomes a sort of laboratory, where hypotheses are tested and the more substantial and material elements are constantly interrogated by other actors who constantly change their angle, expecting to find a breach that would give their – version – of the truth more credibility. It’s beautiful to see.

In Anatomy of a Fall, language and art are paramount actors in this process. These are central topics in the life of the couple of writers. For the trial, they are on a path that might eventually lead them to the truth. They’re pulled to participate in the dispute to determine not only the truth behind Sandra’s husband’s death but also who these characters are.

When words seem to miss the point

The movie begins with Sandra taking part in an interview. She is questioned about her creative process by an enthusiastic student who states that Sandra’s writing is a mixture of reality and fiction – I’ll come back to this element in the next section. Both characters are speaking English and you can hear traces of their mother language in their accents. Some minutes later, we hear Daniel, who had just gone for a stroll with his guide dog, Snoop, screaming in French for his mother.

To bring the mythic Tower of Babel to Anatomy of a Fall with the intention of metaphorizing the multiple and different languages that constitute this scene is a bit of a stretch. There is unquestionable attention from the movie toward the linguistic aspects and interactions.

Sandra is German and her husband, Samuel, is French. They don’t speak each other's language so English is established as their common ground, a language where they can meet and make themselves understood to each other. How could they even become a couple without understanding each other? Did they really? Or were both of them victims of the most cliche tragedy of translation, its natural treason?

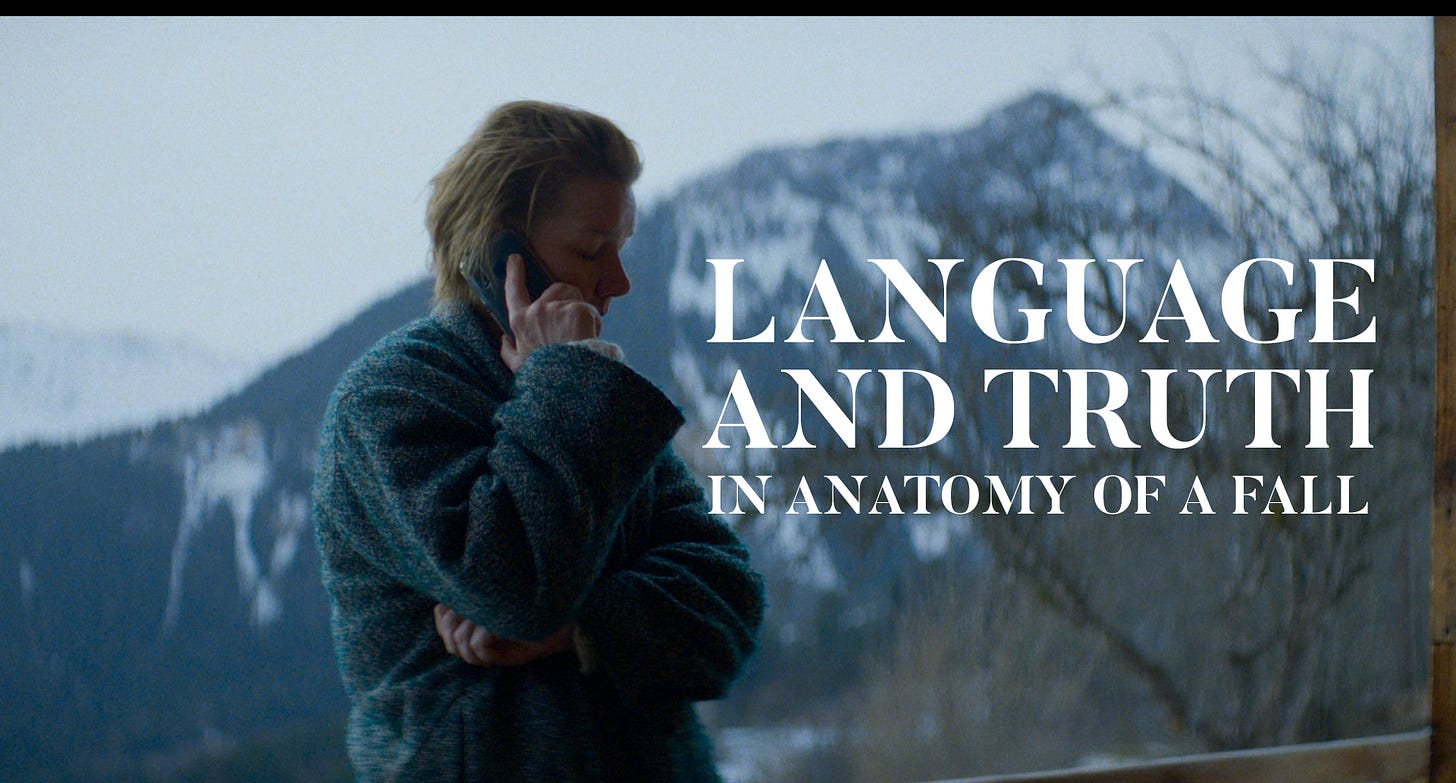

The trial is held in French and, without any consideration about Sandra’s nationality, the government forces her to participate only speaking the language she couldn’t even communicate well with her husband. She tries during the initial days of the trial to only use French. Sandra Hüller, the real Sandra playing the role of the maybe-murderer Sandra, does a splendid job of showing how uncomfortable the character is by not being able to express herself the way she wants. Sandra is a writer. Her craft is based on the idea of picking the right words to pinpoint a unique feeling or other experiences.

In her own trial, she can’t.

Eventually, she gets tired and asks if she can use English. In this specific segment, she argues that the subject in question is complex and difficult to explain. But which topic isn’t easier to discuss when using the words you’re so familiar with? Nonetheless, she understood that the nuances involving that specific topic were too important to neglect by using vague words.

From the moment Sandra starts speaking English, she is capable of expressing her ideas more passionately. When she explains what a relationship between a couple is, Sandra defends a monistic perspective where chaos and order, anger and love coexist. This is how she sees the world around her and English – we never have the opportunity of seeing Sandra using German during the movie – is how she makes this world understandable.

They can’t decide whether the author is dead or not

While I believe it is almost impossible to hold our expectations to know the outcome of a mystery, if those we judge as the unquestionable culprits of the crime are actually guilty, Anatomy of a Fall is far from fulfilling the desire of the audience. We finish the movie without actually knowing if Sandra has violently killed her husband by hitting his head, unbalancing the man who fell to an unceremonious death or Samuel was having a bad day and, well, found relief by jumping from the balcony.

By not giving us an answer, it doesn’t mean that Anatomy of a Fall is not interested in truth. The movie understands well the tricky nature of what we so whimsically take as the truth though. In spite of a straightforward walk toward the hidden – but unquestionable and factual – truth, the movie walks us through a more confused, indecisive path that leads to nowhere. Even so, truth is still one of the most important themes in Anatomy of a Fall.

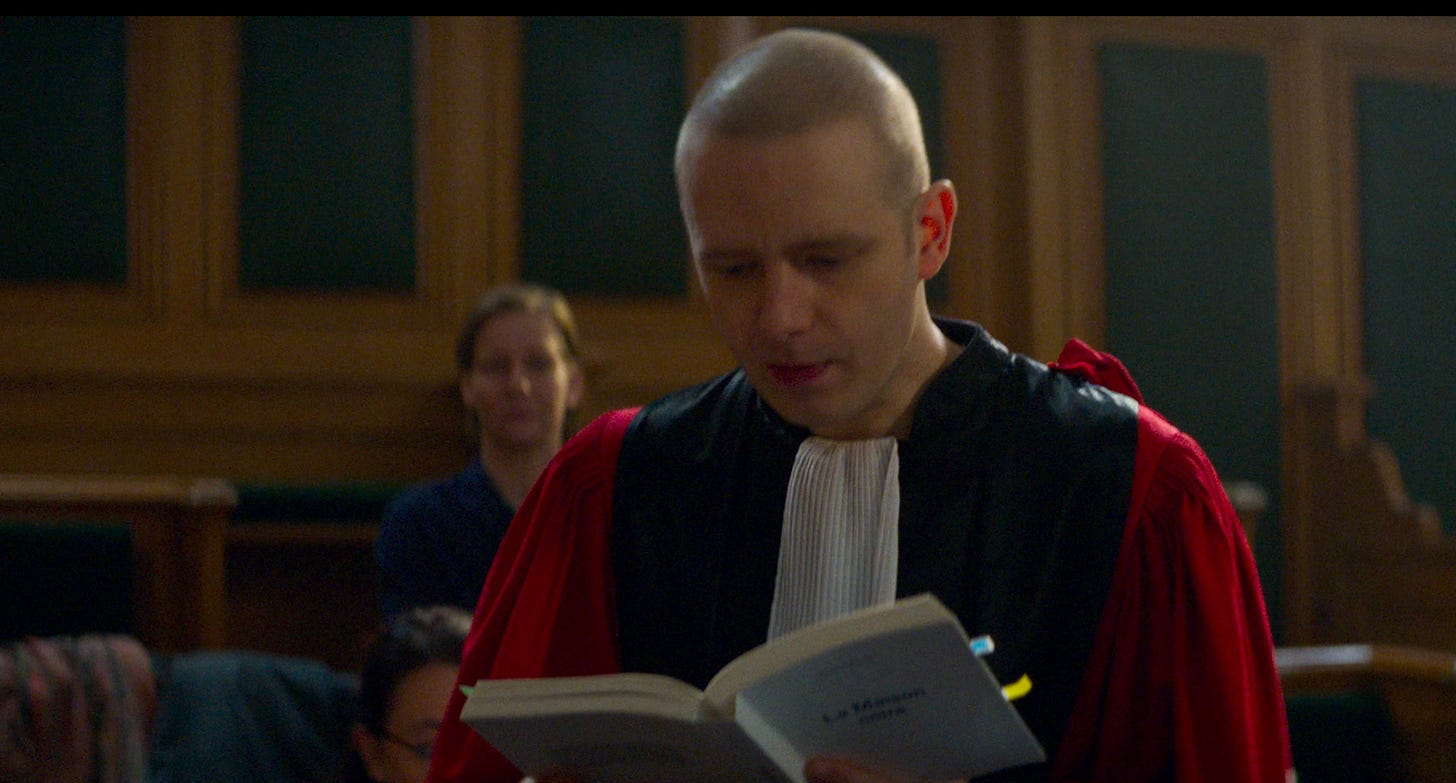

The trial is but a mechanism from which a narrative is weaved to form a truth. I’m not saying that a person stops being dead if the culprit is absolved of all accusations. But the trial is a dispositif that determines whether something happened or not. What is fun – at least for me – is to observe all the movements within such a mechanism and the strategies deployed by it in order to solidify an idea.

In one of the disputes between Sandra and the prosecutor, a curious movement is made by the latter. When the science of the bloodstains analysis has failed and many other formal arguments have already been presented, the prosecutor calls to the witness stand an unexpected character. Art. More precisely, the prosecutor argues that, as a writer, Sandra mixes reality with fiction, that her feelings and desires escape through her writing. Curiously she wrote a female character who thinks about killing her husband. In other words, what is written in her books might indicate Sandra’s inner thoughts. Writing as the window to one’s unconscious.

In many forms, Art is part of this trial, of the movie and of Sandra’s family. From the initial minutes when we have to hear an instrumental version of the 2003 50 Cent song P.I.M.P. to the fact that Sandra and Samuel are writers, art is everywhere. Even their kid is engaged with it, whose evolution in playing Isaac Albéniz’s Asturias serves well to the movie indicating the passage of time. However, regardless of how brief the participation of Art is in the trial, for the first time it is addressed directly and with the purpose of serving as the lenses through which we would be able to see the truth.

What is at stake here is how these characters will understand Art. Depending on the notion they adopt, the prosecutor might be right or wrong. His idea that a piece of art is the reflection of one’s desire would indicate Sandra’s culpability based on what the characters in her novels do, think, and feel. The fictional people and situations she came up with would be taken as silent confessions.

Whereas profiling a person based on their artistic production, psychoanalyzing every word, we have come a long way since Barthes’ Death of the Author to know that the discussions around Art have developed further. Nowadays it feels almost impossible to even grasp the meaning that is constantly questioned and relativized, let alone affirm, from a different perspective, what the author meant by putting a few words together. I’m not an advocate of interpretation as a no-rules realm, where every reading is possible. At the same time, I don’t think writers, painters, game developers, and so on are, when they depict an alien invasion – as an example –, actually exposing the deep-rooted dream of having Earth dominated by extraterrestrial beings.

Quickly, in the movie, Sandra’s attorneys see the kind of narrative the prosecutor wants to create and the path he wants to take the jury. To refute his argument, they simply say “If this is true, then is Stephen King a psychopath?”. There isn’t a good angle from which to counter their point. Many of us have read or watched the movie adaptations of Stephen King’s It and we know that Stephen is not secretly telling us that all he wants is to murder kids as a otherwordly monster. Along the same lines, we could ask if Kafka dreamt of becoming a cockroach or if Clarice Lispect wanted to eat one based on the prosecutor’s argument.

Once this short debate is over, Art is back to the corner, giving space to the humans to speak again. Even so, for a brief moment, Art became the battlefield for the right to say the truth.

Anatomy of a Fall is a very intimate movie where Sandra’s relationship with her husband is the stage from which a chaotic and human play takes place. Bystanders of everything that unfolds in the trial, we’re invited to imagine – investigate! – every piece and their role involved in the fall. For the rest of the movie, Sandra only speaks in English, and no one questions her writing. These two parts of the movie, however, are extremely fun to pay attention to and see how what many might consider mundane topics are subtly affecting the whole experience.